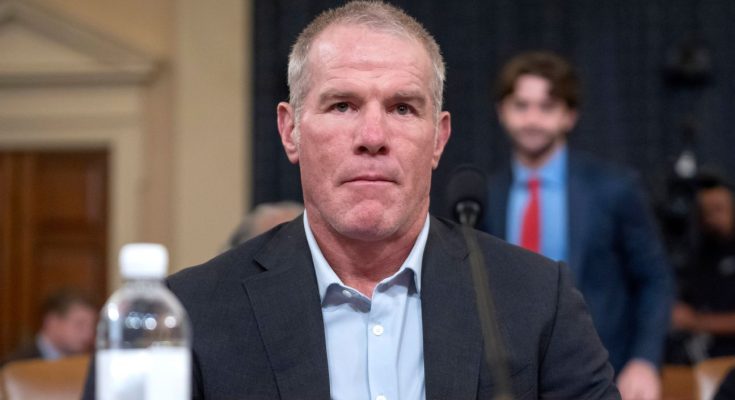

Hall of Fame quarterback Brett Favre disclosed during a congressional hearing on Tuesday that he was recently diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, a degenerative nervous system disorder that causes parts of the brain to deteriorate and affects movement.

Appearing before a House Ways and Means Committee hearing on welfare reform, Favre spoke about Prevacus, a company making a concussion drug that received $2 million of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds. Favre was the top investor in Prevacus, and text messages show he began asking state officials for help securing funds for the company in November 2018.

“Sadly, I also lost an investment in a company that I believed was developing a breakthrough concussion drug I thought would help others,” Favre said during opening remarks. “And I’m sure you’ll understand why it’s too late for me, because I’ve recently been diagnosed with Parkinson’s. This is also a cause dear to my heart.”

A 2020 study found that having a single concussion increased the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease by 57% and having multiple concussions further compounds the danger.

When asked in a 2018 interview how many concussions he suffered, Favre, 54, said he knows of only “three or four” but believes he could have suffered more than 1,000 concussions during his 20-season NFL career.

“When you have ringing of the ears, seeing stars, that’s a concussion,” Favre told the “Today” show. “And if that is a concussion, I’ve had hundreds, maybe thousands, throughout my career, which is frightening.”

The revelation about his health overshadowed Favre’s testimony about TANF, the welfare funds at the heart of the sprawling Mississippi case in which he has been embroiled since 2022. At least $77 million in TANF funds, earmarked for poor families, were diverted to the rich and powerful, according to a 2019 Mississippi state audit. Favre is one of dozens of defendants in a lawsuit seeking to recoup the misappropriated funds. He has denied wrongdoing and has not been criminally charged.

In July, Prevacus’ founder, Jacob VanLandingham, became the seventh person to plead guilty for their involvement in the welfare case, admitting that he used Mississippi welfare money to pay off gambling and other debts.

During the hearing, Favre called for more federal oversight of TANF funds. The NFL legend said the welfare scandal had upended his life.

“I was well received pretty much anywhere I went. That changed, understandably so. The fact that I was branded a person who stole welfare money, that’s the lowest of the low,” he said. “And it couldn’t be further from the truth.”

Favre said he didn’t know what TANF funds were when seeking funding for Prevacus and a volleyball facility at his alma mater, the University of Southern Mississippi. He also received $1.1 million in TANF funds for speeches the state auditor says he never made. He eventually paid back the money.

“I had no way of knowing that there was anything wrong with how the state funded the project,” he said.

Text messages from 2017 show Favre asked whether there was “any way the media can find out” where the money came from and how much. He also asked, “Will the public perception be that I became a spokesperson for various state funded shelters, schools, homes etc….. and was compensated with state money? Or can we keep this confidential.”

Favre said state auditor Shad White, whose office uncovered the fraud, is “an ambitious public official who decided to tarnish my reputation to try to advance his own political career.”

“The challenges my family and I faced over the last three years because certain government officials in Mississippi failed to protect federal TANF funds from fraud and abuse and are unjustifiably trying to blame me, those challenges have hurt my good name and are worse than anything I faced in football,” he said.

White, whom Favre is suing for defamation, told ESPN that he was not asked to testify at the congressional hearing.

Favre, who is under a gag order in the lawsuit, also said the state of Mississippi is using TANF funds to pay attorneys Adam Stone and Kaytie Pickett of law firm Jones & Walker to sue him and other defendants. Stone and Pickett declined to comment, citing the gag order.

Favre, who played for the Atlanta Falcons, Green Bay Packers, New York Jets and Minnesota Vikings, faced a mostly friendly panel at the hearing, with many praising his football career and thanking him for appearing before the committee. He signed a Packers jersey before leaving.

“I’m not mad at you about much,” Rep. Drew Ferguson (R-Ga.) said. “But I’m mad you couldn’t stay with the Atlanta Falcons.”

Favre faced the most direct questions about his involvement in the welfare fraud from Rep. Linda Sanchez (D-Calif.). She asked whether Favre had paid the interest White had demanded on the TANF funds he received and whether he believed “it is acceptable to divert TANF funds away from women who need it the most.”

Rep. John Larson (D-Conn.) told ESPN that committee chairman Jason Smith (R-Missouri) asked Favre to testify because of his celebrity, despite his lack of expertise on TANF. Smith did not respond to an interview request.

Jarvis Dortch, the executive director for American Civil Liberties Union of Mississippi, who also testified at the hearing, pointed out the discrepancy between how ordinary people and celebrities like Favre are treated.

“If someone in Mississippi is … accused of misspending $50 in SNAP benefits, that person’s life will be turned upside down,” Dortch said. “Mr. Favre is right here, and he is accused of misspending a million dollars, and he’s speaking before Congress. Something is wrong when we let that stay in place.”