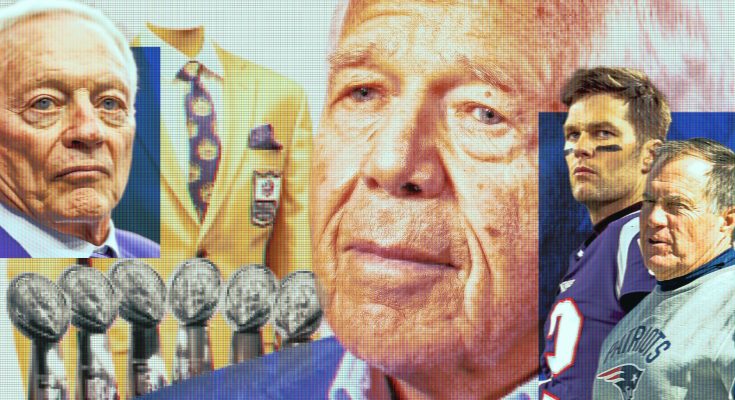

ROBERT KRAFT HAS an $11 billion empire and six Super Bowl rings — five if you don’t count the one Vladimir Putin stuffed into his pocket during a 2005 meeting in Russia. But the New England Patriots boss has fallen short in his lengthy quest for a bronze bust in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

In the past decade, three owners have slipped on a gold jacket in Canton, Ohio. Each time, Kraft, now 83, was on the outside looking in, even though arguably no owner is more deserving.

“There’s no box that Bob Kraft doesn’t check to get into the Hall of Fame,” says Hall of Famer Bill Polian, the former Colts general manager who has twice stood up to argue for Kraft’s induction. “When he didn’t get in last year, I lost sleep over it. I’m still sick at heart about it.”

No current owner has tried harder to get into the Hall — or been denied longer. Beginning in 2012, Kraft’s supporters have lobbied Hall voters on his behalf. Eddie DeBartolo Jr., the former San Francisco 49ers owner, was inducted in 2016 despite losing his team in 2000 because of his connection to an extortion case. DeBartolo has five Lombardi Trophies; Kraft, at the time, had four. Some Hall of Fame voters assured the disappointed members of Kraft’s inner circle that he would be next.

Jerry Jones was inducted in August 2017. The Dallas Cowboys owner threw himself a glitzy party in Canton, headlined by Justin Timberlake. Back in Foxborough, Kraft and his supporters reacted to Jones’ induction with anger and confusion. They seethed that Hall voters didn’t seem to appreciate Kraft’s work to grow the league through media and labor deals, and the Patriots’ unparalleled dynasty.

Kraft saw the selection of his archrival as an insult, a verdict that Jones is more responsible for the NFL’s astonishing success.

“He hasn’t been to the NFC title game in two decades and he gets in?” Kraft told a confidant. “How does that work?”

An escalating campaign

THIS IS A story about the relentless Hall of Fame campaign on behalf of one of the most powerful and influential owners in NFL history, why it remains unsuccessful and how Kraft set out along the way to secretly burnish his own legacy.

Kraft not only hasn’t gotten into the Hall, but not once has the subcommittee even forwarded his name for consideration by the 50 selectors. To his supporters, the annual shutout is a baffling, aggravating mystery.

A dozen Hall voters, who rarely discuss their deliberations, told ESPN that each time Kraft was snubbed, the campaign on his behalf became more urgent and inventive. The selectors lean on a variety of reasons for denying Kraft while approving coaches and a scout from decades ago — and even a referee. The voters said the case for Kraft has been hurt by multiple Patriots cheating scandals, along with a selection system that until now has pitted coaches against owners. They even mention Kraft’s dismissed charges after two visits to a Jupiter, Florida, massage parlor.

Voters also saw — as did many Patriots fans and some former players — two major media projects as pro-Kraft narratives: a bestselling 2020 book, “The Dynasty,” and the Apple TV+ 10-part docuseries of the same name released last winter. Both projects depicted Kraft deftly managing the egos of two all-time greats, coach Bill Belichick and quarterback Tom Brady, to keep the hit-making band together as long as possible.

Some voters told ESPN they believe both projects were intended to juice Kraft’s Hall of Fame candidacy. A Patriots spokesperson adamantly denied the projects were part of any push to get Kraft into Canton. And last winter, Kraft said he had no influence on the docuseries and was “disappointed” with the film.

But Kraft owns the film and television rights to “The Dynasty” book, according to documents obtained by ESPN. That means the book by acclaimed author Jeff Benedict could be turned into a film only with Kraft’s permission. And according to emails, documents and sources, Kraft owns the docuseries, licensed it to Apple and sought editorial control.

Shortly after the book was published, Patriots PR chief Stacey James sent copies to at least five Hall of Fame voters as an argument for Kraft’s induction. The Patriots sent one voter a copy two years in a row.

In a written statement to ESPN, James said it’s “utterly ridiculous” to say the book and docuseries were part of an effort to win Kraft’s induction in the Hall. “It is clear from the inquiries presented in the line of questioning for this story … that there is an agenda being pushed regarding the portrayal of Robert Kraft and the Pro Football Hall of Fame process,” James said.

In early October, a Hall of Fame committee will once again consider Kraft’s candidacy. This time, he will face an easier pathway. In August, the Hall’s board of directors made a monumental change to the voting process by separating coaches and contributors for consideration. Mike Shanahan and Mike Holmgren, considered by voters to be the coaching favorites, will no longer be competing against Kraft and other nominated contributors.

The moment he’s eligible, Brady will catapult into Canton. So, too, will Belichick, possibly in a year if he doesn’t get another coaching job.

For Kraft, the wait is a dozen years and counting.

Nearly invisible

IT IS SAID that most U.S. senators look in the mirror and see a future president. And when most NFL owners look in the mirror, they see a Pro Football Hall of Famer. Few owners have a better argument for induction than Robert Kraft.

But when you walk through the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio, Kraft is nearly invisible.

Where the Patriots dynasty is in the spotlight, there are displays featuring Tom Brady’s game jerseys and Bill Belichick’s hoodie and footballs from famous moments, such as Ellis Hobbs’ 108-yard kickoff return against the Jets in 2007. There’s nothing belonging to the Patriots owner, not even a display of his custom Nike Air Force 1s. Where the Hall lavishes credit on the NFL for helping heal the country after 9/11, there’s no video of Kraft’s famous “We are all Patriots” moment.

There are three photos of Kraft, all on the Hall’s first floor in a confined space that’s easy to miss. He’s in a group photo of NFL team owners. And then his image is on a wall, in a display about stadiums. The Hall uses the same photo, of Kraft holding a Lombardi Trophy, twice within a 4-foot space. One is small; the other is bigger. The bigger one is dwarfed by the photo next to it, of Jerry Jones and his moneyed smirk.

On the Hall’s top floor, in the cavernous, circular room, the bronze busts of the 378 men are displayed. Sixteen of them owned or own NFL franchises. Since 2000, five owners have been enshrined: Dan Rooney of the Steelers, Ralph Wilson of the Bills, Eddie DeBartolo of the 49ers, Jones of the Cowboys and Pat Bowlen of the Broncos.

Of the 16 owners, only Rooney can match Kraft’s six Lombardi Trophies.

This fact continues to confound and aggravate James, the Patriots’ intense public relations man since 1993. As Kraft’s spokesperson and lead Hall of Fame lobbyist, James has called, texted, dined, cajoled and backslapped voters. In recent years, James has emailed voters a six-page dossier that extolls Kraft’s many achievements as an NFL owner. The highlights include buying and reviving the team in the 1990s, winning six championships, cobbling together decades of labor peace with the players’ union, and helping the league land its mammoth TV and streaming rights deal.

Getting Kraft into Canton first occurred to James after watching his boss play peacemaker during the contentious 2011 lockout of players by the owners. When a collective bargaining agreement was finally struck that saved the season, Kraft famously hugged Colts center and players’ union leader Jeff Saturday, who declared: “This doesn’t get done without Robert Kraft.”

When he began lobbying for his boss in 2012, James assumed Kraft’s induction would be a relatively easy sell. “I feel Robert Kraft has no peer when it comes to his contribution to the National Football League,” James said during one of several interviews since June.

But the Hall climb has been especially steep for owners. Until this fall, a subcommittee of 12 people had to advance a candidate to the full voting membership of 50 selectors each January. Usually, only one or two “coaches or contributors” were moved to the full committee. And then that candidate needed 40 votes for induction. The subcommittee has never approved Kraft for a full vote, multiple voters told ESPN.

Every summer, James obtained a list of subcommittee voters. He phoned them, cornered them at Super Bowls, invited them to lunch or dinner or a visit to the owner’s suite, whatever it took to whip up votes. He also sought voters’ advice, asking: How much lobbying is too much? What would be helpful? When should he back off?

Since James started pressing Kraft’s case, there have been 68 Hall voters. James says he has raised Kraft’s candidacy with many of them, using the same argument: If graded on “three legs of the stool” — contributions to the team, the league and pro football — Kraft ranks first among all NFL owners.

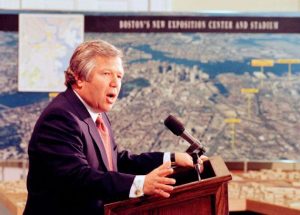

When Kraft, then a 23-year Patriots season-ticket holder, bought the team in January 1994, the franchise was failing. The final home game of the previous season was a rare sellout, filling up because fans feared the team might move to St. Louis.

“I’m a big fan of Jimmy Stewart’s ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’ If Robert Kraft wasn’t born, there would be no NFL team in New England,” James said.

Kraft has done more for the league’s fortunes than even Jones has, James argues. Besides leading the way on owner-friendly labor deals, Kraft is the longtime chairman of the owners’ media committee, which landed 10-year TV and streaming contracts worth $111 billion. And, James contends, Kraft stands alone in helping grow the game internationally.

“Every year,” James said, “I’ve made these same arguments. Every year, voters tell me it’s only a matter of time before Robert gets in.”

Early on, James discovered that influential voters seemed to have “a pecking order” for owners. First, it was DeBartolo’s turn in 2016, then Jones’ in 2017. The back-to-back inductions triggered a lobbying frenzy among other owners looking to get into Canton.

“It was open season, suddenly,” one voter said.

In August 2017, longtime Hall of Fame voter Jason Cole said he sat down for an interview with Kraft and James in Kraft’s wood-paneled office in Foxborough. A few minutes into the conversation, Kraft asked Cole: “How did Jerry Jones manage to get into the Hall of Fame?”

“He’s P.T. Barnum,” Cole said he replied, echoing a sentiment he said he previously had expressed when James called seeking an explanation. “He’s the greatest marketer in the history of the sport.” Cole recalled that Kraft just laughed.

Another longtime voter said Jones’ election “angered all kinds of people because his team doesn’t win.

“The minute he got in, it changed the landscape for some of these owners and made the lobbying even more aggressive,” the voter said. “If Jerry’s in, the owners with egos are thinking, why can’t I be in?”

Pitch for a legacy book

THE PITCH LETTER arrived on Kraft’s desk in early 2018.

Jeff Benedict proposed writing a book about the Patriots dynasty — and sought Kraft’s cooperation. According to a source with knowledge of the letter, the lifelong Patriots fan proposed to set the record straight on Kraft’s underappreciated role in keeping the team in New England and its 20-year run of unprecedented greatness. “It’ll be a book your grandchildren and great-grandchildren will be proud of,” Benedict told Kraft, the source said.

Kraft forwarded Benedict’s pitch to James, who had already been hunting for someone his boss could hire to write a legacy book. A few years earlier, Kraft had tapped a freelance writer to produce a privately published book. The writer accompanied Kraft on a mission trip to Israel, but the manuscript was scrapped. There had been books written on Brady and Belichick, Benedict argued, but “there hadn’t been a book about Robert Kraft.”

Kraft and Benedict met several times before the owner felt comfortable enough to cooperate. Benedict, who declined comment for this story, signed a book contract with a division of Simon & Schuster and then got to work, following Kraft through much of 2018 and 2019, a pivotal year in the Patriots’ dynastic run that ended with a sixth Super Bowl.

Kraft has publicly stated that he stays mostly uninvolved with football matters, but the book showed the owner very much involved — and wanting credit. He gave Benedict details of secret meetings with Brady and Belichick, explaining how he persuaded the two all-time greats to compromise and stay together as long as possible.

Kraft allowed Benedict to eavesdrop on conference calls as the team acquired talented-but-troubled receiver Antonio Brown. Benedict traveled to Israel with Kraft, rode on his private jet, and sifted through reams of privileged legal documents detailing how he bought the team and kept it in Foxborough.

The book depicted how Kraft distanced himself from New England’s cheating scandals but tried valiantly to lobby commissioner Roger Goodell for lightened punishments.

Meanwhile, James continued lobbying Hall of Fame voters; he felt cautiously optimistic 2018 would finally be Kraft’s year. But Denver Broncos owner Bowlen, who had Alzheimer’s disease, was selected. Several voters said Bowlen’s deteriorating health — he died two months before his bust was unveiled in 2019 — was only one reason he edged out Kraft.

That made three owners in four years inducted ahead of Kraft. “Don’t worry, Stace,” a voter assured a despondent James that summer. “Robert Kraft is going to be the next owner in. It’s going to happen.”

That was five years ago.

How selection works

FEW THINGS FIRE up fans more than Hall of Fame debates. But the meetings where candidates are discussed and debated are among the strangest and most secretive deliberations in sports. There’s little transparency, leaving those campaigning for a candidate with no clue on the criteria or how to best champion their guy. They’re flying blind. Votes are confidential, leaks are rare. And a handful of voters, year after year, can block a worthy candidate during lightning-quick Zoom deliberations for reasons left unspoken.

But more than a dozen participants discussed with ESPN how the process works — and why they opposed Kraft or believe he has been denied.

The lobbying, which voters said has gotten more aggressive for all candidates in recent years, starts in the months before a candidate’s first consideration. Then, usually in August or September, committees determine whether players or “coaches and contributors” are worthy of consideration by the full 50 members in January.

At the subcommittee level, a sponsoring voter speaks on the candidate’s behalf for five minutes or so. At times, there is lengthy debate; sometimes there is little said.

Last year, a voter offered an impassioned argument for Kraft. Another voter told ESPN he listened to the argument, kept quiet and then voted for someone else.

“A handful do most of the talking in these meetings,” one veteran Hall of Fame voter says. “Some are silent assassins.”

Part of the problem when it comes to assessing Kraft and the entire Patriots dynasty is factoring in several well-known controversies. A half dozen voters said evolving truths around incidents such as Spygate, Deflategate and Orchids of Asia cloud the team’s greatness.

Kraft’s biggest hurdle among voters seems to be Spygate, Belichick’s 2007 operation to steal opposing coaches’ signals by videotaping them from the sideline, for which Belichick was fined $500,000 and the Patriots fined $250,000. The team also forfeited a first-round draft pick.

A small group of anti-Kraft voters told ESPN they have long harbored concerns that Kraft knew far more about Spygate than he has acknowledged. “Some voters believe he was part of the biggest cheating scandal in NFL history,” a veteran Hall voter said. “That’s a very tough one to overcome.”

Said another voter: “Kraft has distanced himself from Spygate, but it did come up — it has to be considered.”

Several voters also pointed out that Goodell ordered the Spygate tapes destroyed by the NFL general counsel in a Gillette Stadium conference room in September 2007. Goodell, whom Kraft had championed becoming commissioner in 2006, did not order a thorough investigation. “It’s the elephant in the room,” one voter said.

Kraft has denied knowledge of the scheme. In the Apple TV+ docuseries, Kraft says again that he told Belichick he was “a schmuck” for the attempt to steal signs. He also says he fought with the league office to ensure that Belichick was only fined and not suspended.

Polian said he heard these whispered concerns and tried to confront them head-on with fellow voters during his five-minute presentation on Kraft’s behalf last summer. “I told them that Mr. Kraft knew nothing about Spygate in advance,” Polian said, “and [he] took whatever steps he needed to take after it was found out that it did not happen again.”

A few voters said another factor for them is Kraft’s massage parlor charges, which came in February 2019 after he made two visits to the Orchids of Asia. Prosecutors eventually dropped the charges. “We probably need to put a little distance between the massage parlor and the Hall of Fame,” a voter recalled telling James not long afterward.

But Peter King, the 67-year-old retired NFL writer and influential Hall voter who has long supported Kraft’s candidacy, said “there’s a pockmark on everyone in the Hall of Fame.”

“Has there ever been a player, a coach, an owner, a commissioner who has a perfect résumé? Who has never done anything wrong?” King said. “Look at Joe Namath. He threw more interceptions than touchdowns — he’s in the Hall of Fame.”

Another hurdle for Kraft has been structural. Until now, owners and coaches have been considered together, and voters gave more weight to the coaches. “It’s apples versus oranges, and it’s not right,” Polian said. “The way it’s set up hurts an owner’s chances.”

In the five years since Bowlen’s induction, Kraft has been edged out among “coaches and contributors” by former commissioner Paul Tagliabue in 2020; Raiders coach Tom Flores and Steelers scout Bill Nunn in 2021; Eagles coach Dick Vermeil and a referee, Art McNally, in 2022; and Chargers coach Don Coryell in 2023.

When McNally got in, James grumbled to voters that a referee who wasn’t even considered the best ever had somehow won induction over the man he believes is the best owner. Last year, Buddy Parker, who coached the Lions to back-to-back NFL titles in the 1950s, boxed out Kraft as a finalist, although the full committee didn’t vote Parker into the Hall.

“One of the hardest phone calls was to call Mr. Kraft and apologize to him for not being able to get the job done,” Polian said. “He was gracious, and he was tremendous. I still feel very badly.”

“I feel sad,” said ESPN NFL reporter Sal Paolantonio, a longtime Hall of Fame voter. “Kraft deserves to be in the Hall of Fame, in my view, and he should have gone in a long time ago.”

A half dozen voters pointed to James’ lobbying as another intangible in Kraft’s annual Hall of Fame campaign. With each passing year, they say, James has become more insistent and impatient.

“I was repelled by the push — this idea, we’ll do anything to win your vote,” a longtime voter said. “It was never articulated, but it felt that way… I don’t need to talk to anyone. And I can make up my own mind.”

One Hall of Fame voter said he urged James and Kraft’s other supporters to “go lightly — and that’s advice they obviously didn’t take.”

“I’ve told Stacey James this before,” another veteran voter said. “I don’t think he should be in the position to overwhelm people with a mountain of information and a lot of pushing. I’ve told him, ‘I have never seen it work.’ …

“Subtlety goes a long way.”

‘Final cut approval’

WHEN BENEDICT’S BOOK was published on Sept. 1, 2020, Kraft enthusiastically embraced it. Every Patriots season-ticket holder received a copy, helping the book land on the New York Times bestseller list. At a book-signing event inside Patriot Place in Foxborough, Benedict beamed as he autographed hundreds of copies for fans. Meanwhile, some close to Belichick saw the book as a transparent bid to get Kraft into the Hall of Fame.

Soon after the book was published, Benedict had the idea to turn his book into a multipart docuseries. He reached out to Alex Gibney, a prolific, Academy Award-winning documentary filmmaker. Benedict and Gibney had a history. They had collaborated on a critically acclaimed HBO two-part series about Tiger Woods based on Benedict’s bestselling book, co-authored with Armen Keteyian. According to sources involved in the project, the Tiger book and HBO film were “unauthorized,” with Woods receiving no money to appear on camera.

But this would be different. As drawn up by Gibney and Benedict, “The Dynasty” would be an all-access docuseries with 10 episodes of on-camera interviews with the Patriots triumvirate of Belichick, Brady and Kraft, according to the pitch memo obtained by ESPN. Benedict signed a “shopping agreement” with Gibney, which states that Benedict owns all rights to his book, including the TV/documentary film option, and allows the pair to pitch the project together.

Gibney visited Kraft several times at his home in Brookline, Massachusetts. The purpose was for Kraft to get to know and trust the 70-year-old filmmaker. Gibney is known for hard-charging documentaries like “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room” and “Taxi to the Dark Side,” which is about the United States’ torture and interrogation practices during the Afghanistan War. Kraft and the Patriots also had hundreds of hours of behind-the-scenes footage Gibney was eager to use.

Kraft was open to the idea. At first, Kraft suggested leaving out the massage parlor scandal. Benedict’s book devotes six paragraphs to the incident; Gibney agreed to keep it out.

After a series of bids from Netflix, Amazon, ESPN and Apple, Apple acquired the docuseries for $27.5 million, a record sum at that time for a sports documentary.

Shortly after the deal was signed, Kraft hired a powerful entertainment lawyer named Lawrence Shire to represent his interests.

Despite Benedict’s assertion in a signed agreement with Gibney that he owned the TV and film rights to his own book, Benedict’s agent, Richard Pine, revealed in an April 23, 2021, email that his client had “granted Robert Kraft approval over the terms of any deal related to the licensing or sale of film/television rights to his book.”

Gibney and his agents were stunned to learn of Kraft’s stake, but James said it’s standard that Kraft “would retain approval rights over any additional uses of his name, image and likeness and the brand he built.”

Documents show that, through Shire, Kraft sought an equal one-third split of docuseries profits among Kraft, Benedict and Gibney.

Editorial control of the docuseries became a major snag between Gibney and Kraft. Shire demanded creative approvals “to ensure the integrity of the story in the documentary is consistent with that portrayed in the book.” He also sought the right to object to any material that Kraft and his representatives had concluded was “inaccurate, derogatory of, or harmful to” The Kraft Group.

“The ultimate concern here is to protect the image/brand of [The Kraft Group],” Kraft’s representatives said in an email. Such stipulations are increasingly routine in the making of films about celebrities touted as documentaries, according to industry insiders.

When Kraft and his lawyer insisted on “final cut approval” of the film, Gibney refused, according to documents and firsthand sources.

On May 21, 2021, Kraft and the filmmaker talked by phone in a call joined by Shire. According to Gibney’s contemporaneous notes, obtained by ESPN from a third-party source, the call was an attempt to find common ground.

“I gave Robert a preamble about passing the NY Times test,” Gibney wrote. “His response: ‘Who gives a s— about the NY Times? They are wrong about a lot of stuff.’

“Over the course of the call, Robert zeroed in on his ‘negative option.’ I would have ‘editorial control,’ but he would have the right to remove anything that he viewed as harmful to the Patriots ‘brand.’ I said that I would have to run it by Apple.” Gibney explained that Apple had the right, as the financial backer, to be informed of any cuts or be allowed to make suggestions, according to the notes.

“This is just between you and me,” Kraft told Gibney. “You and I can make the deal. Apple doesn’t have to know.”

Kraft continued to insist and seemed to be “getting increasingly angry,” Gibney wrote.

“Alex, it seems to me … that you like Apple more than me,” Kraft said, according to Gibney’s notes.

Shire, who did not respond to a request for comment from ESPN, interjected and agreed with Gibney that the filmmaker couldn’t hide Kraft’s input. The call ended without resolution, according to the notes.

In a statement to ESPN, James said the exchange between Kraft and Gibney never happened. “This question is insulting,” James said. “To suggest that [Kraft] would ask someone to be intentionally deceptive is absolutely egregious.”

Documents show that after Gibney declined to cede editorial control, negotiations between Kraft and Gibney ended.

Then Gibney wrote in an email to Shire: “We discussed the matter of stewardship and agreed that it would not be wise, proper or credible for Robert — who is a subject of the film — to retain editorial control. As the primary creative executive producer, the control of the budget and the final cut of the film must rest with me.”

James said it was Kraft who terminated the negotiations, “much to Gibney’s dismay.”

“Baseless claims built off of irrelevant information stemming from terminated negotiations with someone who is clearly disgruntled should not be used as fact, as Apple is the exclusive rights owner of ‘The Dynasty’ series and Imagine Entertainment retained final say over it,” James told ESPN.

Gibney declined to comment on the specifics of his dealings with Kraft. But in a statement to ESPN, he said, “Viewers can judge for themselves the value of autobiographies or so-called ‘authorized biographies,’ in which it’s clear that the subject has editorial control.

“But I think it’s dangerous for filmmakers and distributors alike to say they have made an objective documentary when, in fact, that is not the case. For those kinds of films — which are becoming well-produced celebrity commercials — there needs to be truth in advertising.”

When the Gibney deal fell apart, Kraft and Benedict searched for a new production company. Within weeks, Kraft struck a deal with Brian Grazer’s Imagine Entertainment to produce “The Dynasty” for Apple TV+.

The profit split in the Grazer-helmed film mirrored the terms in Gibney’s failed negotiation, according to multiple sources with direct knowledge of the arrangement. The sources said they were uncertain whether Kraft maintained editorial control in the film produced by Grazer, his close friend.

‘A little disappointed’

FAST-FORWARD TO January 2024. Brady is retired. Belichick is essentially fired by Kraft. A close circle at the league office had early access to “The Dynasty.” Chatter soon spread that the docuseries was “horrible for Belichick” and was an obvious Kraft infomercial, with the words “Kraft Dynasty LLC 2024” at the end of each episode’s credits as proof. NFL Films had initially been announced as a co-producer of the docuseries, but league executives decided to drop the affiliation.

In February, when “The Dynasty” was released, the public — and several former Patriots — said it felt transparently pro-Kraft and anti-Belichick. The series whizzed past the Patriots’ back-to-back 2003-04 Super Bowl wins but brought on camera luminaries such as Rupert Murdoch to ruminate on Kraft’s leadership. Entire episodes were devoted to team scandals involving anyone but Kraft. Just as Gibney had agreed to do, the filmmakers ignored Kraft’s 2019 charges.

In the end, though, the series was less the definitive celebration of greatness that Kraft had envisioned and more like another messy chapter in the dysfunctional family drama. Like many Patriots fans, Kraft insisted that he, too, was disappointed with many aspects of the docuseries, which he denied having any control or say over.

“I felt bad that there was so much emphasis on the more controversial and, let’s say, ‘challenging’ situations over the last 20 years,” Kraft told reporters last March. “I wish they had focused more on our Super Bowl wins, our 21-game win streak. So, a little disappointed that there wasn’t more of a real positive approach — especially for Patriot fans who have lived the experience with us.”

With fans decrying the film and blaming Kraft, James told reporters that Grazer had produced the documentary as a favor to his old friend. Grazer also said the project was a byproduct of his friendship with Kraft, telling Deadline last February: “Someone else was going to do it and then Kraft said, ‘Well, Brian, if you were going to do it then I would love to do this with you,’ because neither one of us considered each other in that way, just as friends. And I said, you know, I’d love to do it.” ESPN could not reach Grazer for comment.

The docuseries’ director, Matt Hamachek, declined several interview requests. “The filmmakers maintained full editorial control from start to finish and would not have proceeded without that level of independence,” spokesperson Katie Conklin said in a statement given to ESPN on Hamachek’s behalf.

Some Patriots fans criticized the negative portrayal of Belichick. “To be honest, my head coach is a pain in the tush,” Kraft says in the docuseries, “but I was willing to put up with it as long as we won.”

Even Belichick highlighted his harsh treatment in the film during the Tom Brady roast in early May. With Kraft looking on, Belichick joked: “Seriously, I’m so honored to be here for the roast of Tom Brady on Netflix. It’s not to be confused with the roast of Bill Belichick on the 10-part Apple TV series.”

By the end of the night, it was clear that “The Dynasty” had not done Kraft’s legacy any favors.

‘A silly misstep’

THROUGHOUT THE OFFSEASON, Kraft found himself in the strange position of distancing himself from his own documentary. The film was panned by Patriots fans, as well as some Hall voters.

For his part, James has told voters he won’t be doing any more lobbying.

When told about Kraft’s hidden stake in “The Dynasty” book and documentary, a handful of Hall of Fame voters said that it might impact their consideration of Kraft, and that it won’t do him any favors. One anti-Kraft voter said simply, “I’m not surprised.”

Others said that they don’t care and that it shouldn’t matter at all — Kraft is long overdue for his gold jacket. “These are misdemeanors,” one voter said. “Bad judgment misdemeanors.”

Besides, now that the nine members of the Hall’s contributors-only committee will consider owners without competition from coaches, Kraft’s chances appear to have improved, voters say. Two voters briefed on the membership say that “a majority” of the nine members are Kraft supporters.

Cole, the veteran Hall voter, said Kraft’s bid to covertly manage his legacy “just shows how desperate he is, but he’s desperate because no one deserves to get in more than him.”

“It’s a silly misstep,” Cole said. “It just shows the mindset of a man who wants his legacy recognized while he is still alive.”

Polian called the docuseries backlash an outlier in Robert Kraft’s charmed life of winning streaks.

“I just saw it as an interesting documentary,” Polian said. “It has the Kraft point of view, the Patriots point of view, which is understandable.

“Winners write history. Losers go home.”